Designing Project Culture on Purpose

Choose Your Project Culture Before It Chooses You

Some projects feel hard, but satisfying. Others feel hard and exhausting in a way that lingers long after the work is done.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that the difference usually isn’t the scope, the timeline, or even the complexity of the work. It’s the project culture.

How decisions get made.

Who’s involved (and who isn’t).

How much ambiguity people are expected to tolerate.

Whether collaboration is encouraged or focus is protected.

How much learning is required versus how much execution is expected.

Every project has a culture, whether we name it or not. Most teams just…drift into one.

And that’s where unnecessary friction shows up.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how leaders can be more intentional about avoiding the drift. How can leaders choose the kind of project environment they’re creating instead of discovering it halfway through when people are already frustrated?

One simple way to do that is by borrowing a classic strategic thinking tool and applying it to how work actually gets done.

A Simple Way to Make the Invisible Visible

I’m a big fan of tools that don’t require a special certification or a 40-slide deck to be useful. The humble 2×2 grid falls squarely into that category.

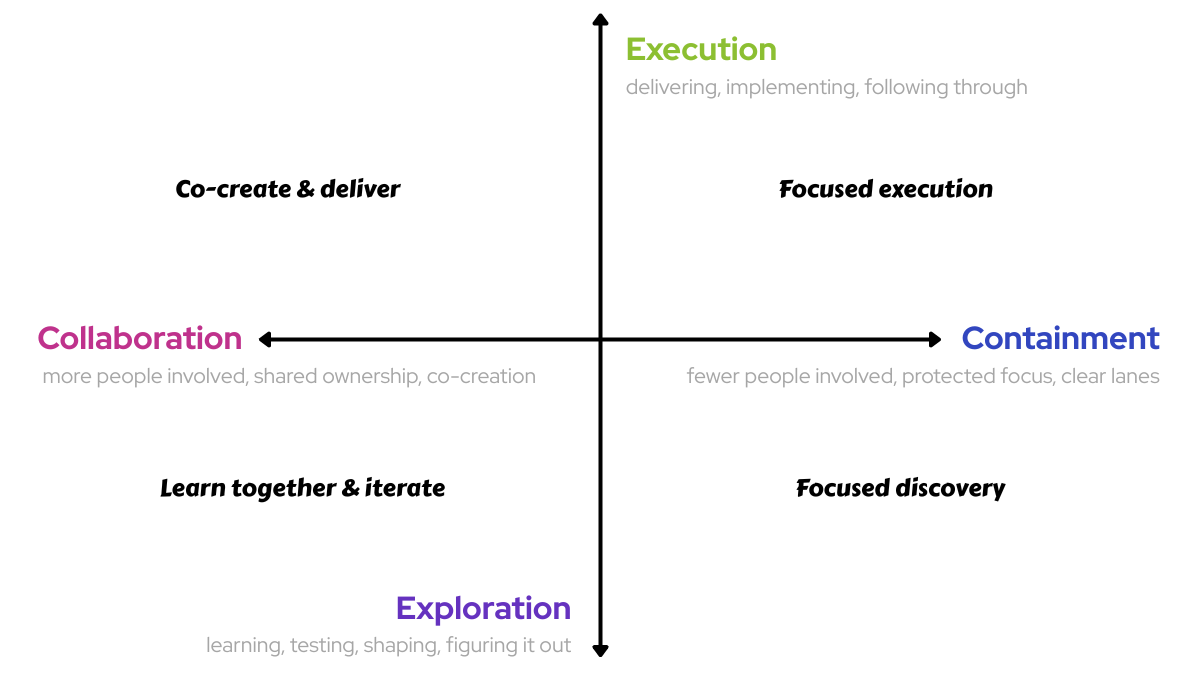

Not as a way to label teams or rank performance, but as a way to consider opportunity cost and to force intentional tradeoffs. For project work, the following grid isn’t the only set of parameters, though I’ve found this framing especially helpful:

Collaboration ↔ Containment

Exploration ↔ Execution

Put together, these two dimensions help surface a question most teams skip:

What kind of project culture does this work actually need to succeed?

Before we look at real examples, consider the following context for the axes:

Exploration: learning, testing, shaping, sense-making, discovering the “right” answer

Execution: delivery, efficiency, consistency, follow-through, implementing something largely known

Collaboration: many voices, shared ownership, co-creation, cross-functional input

Containment: limited stakeholders, clearly defined lanes, protected focus, reduced cognitive load for others

There’s no “best” quadrant here. There’s only fit.

Problems arise when a project needs one kind of culture but is run as if it has another.

Three Projects. Three Very Different Cultures.

To make this concrete, here are three project scenarios I’ve worked with in recent years. All three were valid. All three were successful. And all three lived in very different places on a grid…because their needs were different, of course.

1. A Higher Education System Migration

(High Collaboration + High Execution)

A university was facing a significant student information system migration. Their long-time provider was sunsetting the application, and there was a hard timeline attached.

This project involved:

stakeholders from across the university

a new software vendor

external consultants

internal teams with deep institutional knowledge

The stakes were high. The margin for error was low.

This project had to be collaborative. There were too many interdependencies and too much institutional context for it not to be. At the same time, it also demanded strong execution: clear decision-making, defined roles, disciplined timelines.

When this kind of project isn’t intentionally designed, it can quickly overwhelm people. But when leaders acknowledge upfront, “This will require a lot of collaboration and structure,” they can build in the support and pacing people need to stay engaged.

The culture matched the work.

2. A Nonprofit, a Grant, and a Narrow Window

(High Containment + High Execution)

In another case, a social services nonprofit had grant funding they needed to finish using up relatively quickly. The goal was a very specific recruitment and relationship-building initiative tied directly to the grant requirements.

Instead of pulling internal staff into yet another project, they brought in an external consultant to focus exclusively on this work, with a clear plan to train an internal replacement at the end.

Only one person was deeply involved day-to-day. This wasn’t exclusionary. It was protective.

Containment preserved focus, speed, and sanity…especially for a nonprofit team already stretched thin. Trying to make this project highly collaborative would have slowed it down and increased cognitive load without improving the outcome.

This is an important reminder: not every project benefits from broad involvement. Sometimes the most humane choice is to limit who carries the work.

3. A Consulting Firm Expanding Its Content Strategy

(High Collaboration + Exploration → Execution)

In a third scenario, a consulting firm wanted to expand its digital content presence without distracting consultants from their billable work.

The early phase of this project leaned heavily into collaboration and exploration:

internal “show and tell” sessions

shared learning

building understanding before building assets

Over time, the culture intentionally shifted toward execution: repurposing internal materials (with thoughtful redaction) into external content, streamlining workflows, and clarifying ownership.

What made this work wasn’t just the strategy — it was the sequencing.

Leaders anticipated where distraction and overload might occur and designed the project culture to protect capacity while still moving forward.

The project’s culture evolved as the work evolved.

The Practical Takeaway: Choose the Culture Before You Choose the Plan

Here’s the part I wish more teams did before launching into project work:

Pause.

Sketch the grid.

Have the conversation.

Not about tasks or timelines, but about how this project needs to feel to succeed.

A few questions I often ask teams:

Does this work require many voices, or protected focus?

Are we primarily “learning our way forward,” or executing something already known?

What tradeoff are we intentionally making? Which opportunity cost is the lesser evil?

Where might people feel friction if expectations aren’t clear?

When leaders set expectations about project culture upfront, something powerful happens: people stop guessing.

They understand why collaboration is heavy (or intentionally light). They know whether ambiguity is expected or minimized. They can align their energy instead of burning it up with frustration.

This is one of the simplest ways to reduce change fatigue before it sets in.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In small and mid-sized organizations — especially nonprofits and consulting firms — capacity is always tight. People are already juggling multiple priorities, roles, and emotional loads.

When project culture is misaligned, it doesn’t just slow work down. It erodes trust.

But when leaders design the environment intentionally, project work can actually become a stabilizing force…a place where clarity, momentum, and shared understanding grow.

You don’t need the “perfect” culture. You just need the right one for the work in front of you.

And that choice, made early, is one of the most people-centered moves a project leader can make.

If your projects tend to feel heavier than they should, it might be a sign that the culture around the work needs a little more intention.

This is the kind of work Mosaic BizOps supports as a fractional partner — helping teams design project and change environments that reduce friction and build momentum. We’re always happy to talk through what that could look like for your organization. Let’s chat.